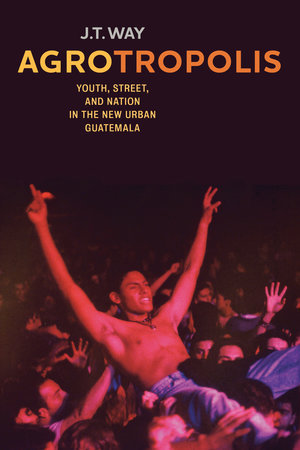

By J. T. Way, author of Agrotropolis: Youth, Street, and Nation in the New Urban Guatemala

As a scholar whose research applies directly as testimony in asylum cases, I am well-versed in why thousands of Guatemalans are fleeing for their lives. I explain many of these realities in my new book, Agrotropolis: Youth, Street, and Nation in the New Urban Guatemala. A fragile democracy in a country torn up by war and genocide gets gutted in its infancy as neoliberal policies shrink the state. Local thugs make towns their fiefdoms as lawlessness, corruption, and common and organized crime sweep the landscape. Neighborhood watch patrols become vigilante lynch mobs. Gender-based violence rises to the level of femicide. Youngsters make it through high school but find no work in an extractive economy propped up by migrants’ remittances and aptly symbolized by unregulated offshore banks. Hopes for a better life around the end of the war in 1996 fade in the next two decades as a “war of all against all” brings more violence and despair.

But alongside this darker story, the book also unearths a happier and just-as-human side of this poly-ethnic, multilingual nation’s history from 1983 to the 2010s. It focuses on new baby-boom generations that have made Guatemala one of Earth’s youngest nations. The life stories of these young people coincided with the rapid urbanization of the countryside as secondary and tertiary cities exploded in size and small, agrarian municipal centers and their surrounding villages evolved into what I call “agro-urban” space. The youth who came of age on Guatemala’s urban and agro-urban “street”—the calle, or KY in internet slang, a physical setting but also one with a vibrant life as a cultural imaginary—are cultural creators who have redefined what it means to be Guatemalan. In dialogical and contested processes that involved youth of all backgrounds, but were led primarily by Maya and mestizo youngsters from the poor majority, Guatemala’s new generations have overthrown centuries-old caste and race-based codes of servility and deference and given rise to an alternative, bottom-up popular nationalism.

Agrotropolis draws on a varied archive of primary sources, as well as my ethnographic field work in a nation I’ve explored since 1991 and lived in from 2002 to 2012. It maps documents on politics, economics, and development against a kaleidoscopic array of cultural productions. It’s the first book to tell the story of Guatemalan rock nacional, with genres ranging from death metal to grunge to Maya rock-folk fusion and Spanish and Mayan-language rap (you can find some sample videos below). I examine ad campaigns and pop-culture websites, blogs, and Facebook and YouTube posts and comments. The book also traces a florescence of new novels and films and an explosion in photography, painting, wild-style graffiti and break-dancing. All of these art forms arose in fertile dialogue with a “Maya power” movement that spearheaded a cultural sea-change in the nation. Street art, slang, style and fashion, leisure activities, and even the postures and gestures wrapped up in people’s “forma de ser” (way of being) all find a place in this history.

“Guatemala’s new generations have overthrown centuries-old caste and race-based codes of servility and deference and given rise to an alternative, bottom-up popular nationalism.”

J.T. Way

In dialogue with the violent and dangerous world around them, young Guatemalans drew on a history of rebellion and resistance, ethnic pride, and local traditions as they contested and retooled national identity and created new—and often very ribald—idioms of belonging. As they did so, agro-urbanizing streets and neighborhoods came to join their big-city counterparts in a real-and-imagined cultural commons that not only formed the Guatemalan “agrotropolis,” but also linked it to increasingly cosmopolitan “city” space around an urbanizing planet. In Guatemala, as elsewhere, the post-Cold War generations are often dismissed for their supposedly mindless and apolitical embrace of consumer culture—that is, when they’re not being cast as pathological criminals or portrayed as perfect, innocent victims. Pura paja, vos…B.S.! It remains to be seen whether their creativity will be answered with social or economic justice. But it is clear that new-generation Guatemalans, just as much as their elders, have been powerful cultural creators and historical actors.

Agrotropolis makes a great ending to undergraduate Latin American history or related LAS classes, as well as reading for grad seminars, urban studies and Global South classes. It arcs from Cold-War genocide to the 2010s and is studded with references to global economic changes and politics around Latin America. I’ve written it to work with a simple “skim over the heady parts” instruction for less advanced or time-pressed undergrads and have used prose that captures the tenor of how young people speak on the calle. Agrotropolis also has a soundtrack, and cueing up the videos will make for engaging classroom sessions. But beyond all this, it also explains why so many Guatemalans, and by extension, other people from the Northern Triangle, are fleeing for their lives to seek asylum in the north.

Sample Clips

Ads and Comedy

Big business, like government youth programs, glommed onto what was happening on the street. This ad in a campaign for Tortrix (a snack food company owned by Pepsico) produced by BBDO Guatemala became a part of the popular culture. It shows an uptight man transformed into an authentic “chapín”—slang for Guatemalan—when he eats Tortrix and speaks in proper slang, saying “chulo tu chucho colocho,” meaning “cute mutt, curly!” Tortrix/BBDO Guatemala, “A este chapín le faltan Tortrix (Perro),” 2008, uploaded by sandovalescobedo.

This 2009 comedic video (Walter Soberanis, “Radio Nahualá) about the agro-urban town of Nahualá went viral in Guatemala. This clip is best for Spanish speakers. It’s a classic example of Guatemalan humor, and is covered on page 185 of Agrotropolis. While it pokes fun at agro-urban Maya life and is politically incorrect in the extreme, it is beloved in the region and around the nation.

Music

These two clips are Spanish raps by Bacteria Soundsystem Crew, formed by artists who grew up in dire poverty in Guatemala City and began performing in the 1990s. “La Virula” (Bicycle), from 2007, sings of pedaling around the city (because “I don’t have a car”). It resonated with agro-urban youth around the nation. The second, “Lo que veo” (What I see) is from 2011. It slams President Colom for touring the country to promote “governing with youth” when “what I see” is exploitation, crime, and misery.

This haunting 2012 rap in Mam by Shat Juárez (Roberto Juárez Lucas) mixes agrarian and urban images. The page has a Spanish translation of the lyrics, but even without this, the raw emotion comes through clearly.

Fernando Scheel, a musician who gained fame in the 1990s, later worked with many Maya artists. Here Raquel Pajoc raps in Kaqchikel of moving from Sololá to Guatemala City to study. In 1996, the government invited Scheel and Anneliese Magermans to write the official theme song for the signing of the Peace Accords, “Hablemos de Paz” (Let’s speak of peace).

Sara Curruchich grew up in Kaqchikel-speaking San Juan Comalapa, a center of the Maya cultural renaissance. In 2012, she briefly joined a national rock group, and she performed with the Dresden Philharmonic in the same year. This song, “Ch’uti’ xtän (Niña),” is from 2015.

This post is part of our #LASA2021 conference series. Visit our virtual exhibit page to get 40% off the book.

About the Author

J.T. Way is Associate Professor of History at Georgia State University and author of The Mayan in the Mall: Globalization, Development, and the Making of Modern Guatemala. He lived in Guatemala for ten years and has extensively studied the country’s popular class.

Photo: The author, second from the left, while interviewing members of Ijatz Crew, a group of Tz’utujil-Maya b-boys, in San Pedro La Laguna in 2016.