By Colin McFarlane, author of Fragments of the City: Making and Remaking Urban Worlds

I was standing in front of two side-by-side pictures, both black and white images of houses on an ordinary street. When I stood back, I realised that the photos were in fact of the same house. One image of the house was intact, the other broken-up – fragmented in mid-demolition. It was the graffiti on the wall that made me realize this was the same building: ‘Don’t vote, prepare for revolution.’

These two photographs are part of an exhibition currently showing at the Laing Art Gallery in Newcastle, northeast England – The Last Ships, by Chris Killip. They offer glimpses of streets around the city’s River Tyne in the late 1970s, capturing the twilight years of shipbuilding, and the fragmentation of the area’s built and social worlds.

Walking out of the gallery, you might see a second set of fragments: the half-built network of elevated walkways in the city (see Figure 1). Developed in the 1960s under the city council leadership of the controversial T Dan Smith, the walkways separated motorway traffic below from pedestrians above, and were inspired by post-war modernist planning ambitions that led to large-scale redevelopment and demolition in Newcastle and beyond. Some of the walkways are still accessible, but they are generally not well used. Here and there they linger in mid-air as sections that come to abrupt and incongruous stops, fragments of another time and urban aspiration.

Cities are becoming increasingly fragmented materially, socially, and spatially. The key drivers vary from place to place, but there are some common causes of fragmentation, including exclusion from land and decent housing, leaving more and more people in insecure, rented homes; a lack of decent and affordable infrastructure and services, with the basics becoming more expensive for lower-income groups; and local and central states that either lack resource or political will to seriously tackle poverty and inequality (see Figure 2). But how is life lived in the fragment city? How are its conditions being contested? And what forms of knowledge, practice and possibility emerge when we examine the fragments of the city?

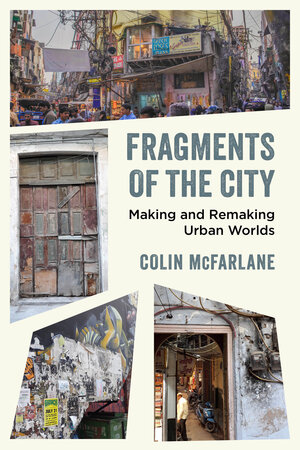

These are the questions which guide my new book, Fragments of the City: Making and Remaking Urban Worlds. In Newcastle, close to where I live, fragments tell all kinds of stories. These are the bits and pieces of the city that become caught up in stories of the urban change, politics, and everyday experience. I treat fragments not just as nouns, but as verbs — processes as much as things, with different kinds of meaning attached to them. Sometimes fragments are routine parts of urban experience, at other times they surprise and might even jolt new ways of seeing an urban issue or concern.

I focus on fragments and their interactions with residents, activists, artists, writers, and others. I explore not just material fragments, but fragments of knowledge too. These are forms of knowledge and ways of knowing that are typically marginalised by dominant cultures, actors, groups, and power relations, and which can present clues to different ways of understanding the urban condition and its possibilities.

The book itself is also an experiment with fragments as a form of written expression, with fragments of text that describe brief encounters with urban sites across the world. Each encounter acts as an evocation or provocation, with glimpses into conditions that collectively generate insight into the larger urban condition. I draw on and juxtapose research in several cities to argue that the relations formed around fragments can help us to understand what it means to be urban.

In Mumbai, I explore how fragments of infrastructure become central to urban struggle, while in Cape Town I trace an example of how fragments become political weapons, contesting inequalities of class and race. In Berlin, I consider the controversy over the treatment of newly arrived refugees in 2015, largely from Syria, who struggled for periods with deeply inadequate provisions of toilets, food, and shelter. In Kampala, I discuss how a group of poorer residents make their way in the city, and how they cope with and seek to move beyond an urbanisms of fragments, while in Hong Kong and New York I reflect on the possibilities – and limits – of coming to know fragments through walking the city. Beyond these cases, the book draws in writing, activism, art and stories of urban change that include London, Los Angeles, São Paulo, Glasgow, and – to return to where I began – Newcastle. Paying attention to these fragments unveils resources for making sense of our increasingly urban world, and possibilities for making and remaking the city.