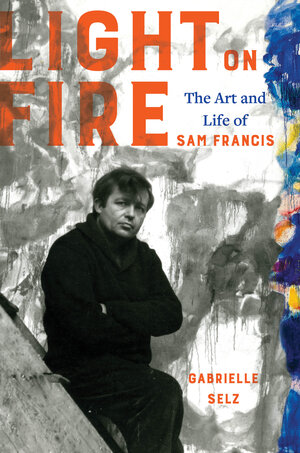

Out today, Light on Fire: The Art and Life of Sam Francis is the first in-depth biography of Sam Francis, the legendary American abstract painter who broke all the rules in his personal and artistic life.

The following passage is an excerpt from Chapter 4 of Light on Fire: The Art and Life of Sam Francis. In 1947, Sam Francis and his first wife, Vera Mae Miller, moved to Berkeley so that Sam could finish his education. Before he’d enlisted in the Air Corps in 1943, he’d completed two years as an undergraduate in Pre-Med. After suffering from Spinal Tuberculosis, he’d taught himself to paint while encased in a plaster corset. Now, he returned to U.C. Berkeley, determined to study art become an artist.

The second university in the country to open an art department, UC Berkeley had a reputation for intellectual rigor. Even for an art degree, the academic requirements were strenuous. They included art history lectures as well as studio work. This set the program apart from traditional art schools, which focused almost exclusively on studio work. In the late 1940s, UC Berkeley’s art department was still dominated by the ideas and methods of the German transplant Hans Hofmann. A native of Bavaria who had studied in Paris before World War I, Hofmann synthesized German Expressionist energy, Fauvist color, and Cubist structure into his famous principle of “push-pull” in art. According to Hofmann’s philosophy, movement and drama were created in modern painting not by forms in illusionary space but by opposing compositional forces: warm versus cool colors, and hard, geometric shapes versus fluid, biomorphic ones. Though Hofmann taught only two summer sessions in Berkeley (1930 and 1931) before starting his own school in Provincetown, Massachusetts, many of his protégés ran Berkeley’s art department, including Erle Loran, James McCray, and Glenn Wessels. They carried on his rhythmic methodology.

Right from the start, Sam charted his own course as an art student. Because of pain and the handicap of his back and leg brace, he rarely attended classes. Of his relationships with his professors, he said, “They did not pay much attention to me . . . they let me go on, which was the best.” Another student remembered thinking Sam was a smart-ass who preferred pursuing his own ideas. “There’d be a still life set up, and Francis would come in and do the blue version, the green version, the red version, the yellow version, while the rest of us were struggling just to get at what it looked like.” Sam could be a smart-ass, but, even as a student, he trusted his intuition about painting. His isolation in the hospital had amplified his independent, auto- didactic nature. Regarding his restricted use of color, he said, “I approached color in the beginning with the caution of a big game hunter in a new territory because I felt that I was dealing with something that could swallow you up. Therefore, I was very much involved with one color at a time.”4

In one of his first painting classes, taught by Margaret Peterson, a prominent painter steeped in the influence of primitive art, Sam met fellow students Fred Martin and Jay DeFeo. Both were a few years younger than Sam. Soon Martin was sharing a painting studio that Sam found in an old dairy barn near the Berkeley campus. DeFeo remembered visiting them and thinking they were “doing some very progressive things . . . .They were a little more aggressive than I was about getting out, crossing the Bay and experiencing some of those people like Rothko and Still when they came to teach at the California School of Fine Arts.”5

The back trouble that prevented Sam from attending classes regularly didn’t stop him from exploring San Francisco. By this time, he was absorbing and assimilating various sources into his personal art education, emulating not past but contemporary styles. He spent a good deal of time at the Legion of Honor with his pad and pencils, copying the soft biomorphic forms in the work of Arshile Gorky. He viewed Jackson Pollock’s defining painting, Cathedral (1947), an early drip canvas in black and white. At the Legion and the San Francisco Museum of Art, he discovered the small, Asian-inspired paintings of looping lines by Mark Tobey and the bold, classical forms of Robert Motherwell. In 1946, the San Francisco Museum of Art had established the country’s first rental gallery, which allowed visitors to rent artworks either for study or as a prelude to purchasing. Martin and Sam would sometimes pool their resources and rent paintings to take to the studio for prolonged examination.

Though some artists and teachers figured prominently in Sam’s education, he never attached himself to a mentor. In all likelihood, he would have found that kind of relationship too confining. Without a mentor, he had no set of rules to struggle against. Unrestricted, he was free to dis- cover and absorb his own influences.

There were, however, three artists whose work guided him at this junc- ture of his education: Clyfford Still, Mark Rothko, and Edward Corbett. Never studying formally with Still or Rothko, Sam nevertheless came into contact with their paintings and their ideas about art’s mythic status dur- ing his frequent visits to San Francisco.

Back in 1946, while Sam was still in the hospital, Still had mysteriously appeared at the doors of the California School of Fine Arts, dressed in his customary black coat and holding crumpled snapshots of his paintings. Captivated by the man and his work, the school’s director, Douglas MacAgy, hired him to fill a vacancy in the painting department. An authoritative and commanding man, Still soon took over the graduate department. Like Sam, he was mostly self-taught. Born in 1904 and raised on a wheat farm in a remote, impoverished area in Alberta, Canada, Still learned to paint by copying reproductions found in magazines. For a year, he studied art at Spokane University, moving in rapid succession through explorations of old masters to modern ones, but then dropped out, in order, he said, “to paint my way out of the classical European heritage.” Unlike the Hofmann disciples at Berkeley who believed in learning from the rich academic past, Still challenged his students to follow an intuitive path and “cut through all cultural opiates.” Though his puritanical, moral streak and superior atti- tude alienated many on the faculty, including David Park, his rejection of tradition inspired his students.

Sam, too, had worked his way through the history of painting. He viewed Still’s solo exhibition at the Legion in 1947, and the large, dark canvases cut through with jagged bolts of color left an indelible imprint on him. They proclaimed the grandness of the landscape and an expansive artistic vision that felt akin to his own aspirations. After the show at the Legion, Still noticed Sam “hanging around the studios on weekends talk- ing to the students.” In this way, Sam got close enough to Still’s messianic intensity without getting burnt by the great man’s fire.

However, Still’s heavily textured opaque paint did not resonate with Sam. In a class with Erle Loran at Berkeley, Sam appeared one day with a painting Loran thought was influenced by Still “but more sensitive in color.” Sam had replaced the heavy, opaque oil paint that Still preferred with watercolor, giving his canvas a more delicate, translucent finish. By this time, he had become attracted to the romantic, thinner surfaces of Rothko and Corbett.

In the summers of 1947 and 1949, at Clyfford Still’s invitation, Mark Rothko came west from New York to teach in San Francisco. Rothko, an urban man compared to the rural Still, brought with him the idea that color could carry the main burden of the painting. During this period, he was still creating quasi-abstract images in pinks and blues, but soon he started working with simple, rectangular floating shapes. The thinly colored surfaces and sensitive edges of a Rothko painting contrasted with the forceful, rugged hardness of a Still. Rothko seduced the viewer, while Still’s paintings were confrontational. Several of Sam’s paintings from 1949 show him exploring Rothko’s rectangular format with softly blurred and rounded edges but with a more dappled brushstroke.

In the spring of 1949, Sam studied with Edward Corbett, who had previously taught at the School of Fine Arts and was now an instructor at Berkeley. He was a witty, sensitive man, fond of quoting Kierkegaard. At the time of Sam’s class with him, Corbett was painting moody abstractions that evoked the Bay Area’s billowy fog. Eventually, Sam would take Corbett’s airiness—his light and atmosphere—to another level. He would incorporate a luminosity not present in Corbett, integrating landscape and abstraction. In fact, California Grey Coast, Sam’s early painting from Monterey, had already accomplished this atmospheric melding of land- scape with his artistic consciousness.

With the oil painting For Fred (1949), Sam’s process coalesced. Dedicated to his friend Fred Martin, it marks the fusion of his art education with his personal themes. Small, saturated, deep red organic forms swarm across the surface like gathering masses of blood or bacterial cells. The painting incorporates the push-pull energy of Hofmann, the rectan gular shapes of Rothko, the fluidness of Corbett, and the biomorphic shapes Sam had studied in Gorky’s work. Its size conveys the dominance of Clyfford Still. At fifty-nine by forty inches, it was Sam’s largest painting to date. Most importantly, as William Agee points out, it was Sam’s “first foray into the brilliant color that characterizes his later work.”

During the two years it took for Sam to complete his bachelor’s degree in art, Vera held out hope that they would start a family. But by the fall of 1949, when Sam began working toward his master’s, Vera was not pregnant, and it had become evident that Sam did not want a settled, faithful married life. Their love for each other had been primarily based on a shared history and need: Sam’s to be cared for, Vera’s to caretake. Now they separated. Moving out of married student housing, Vera found an apartment with a friend, and Sam rented a room a few blocks from cam- pus at 2620 Regent Street. There he slept in a single bed with rows of his framed canvases stacked deep against the walls. Friends since they were teenagers, Sam and Vera continued to spend time together, even when living apart. With Fred Martin, they looked at art, listened to jazz, and enjoyed the emerging beatnik scene in North Beach, where the sign out- side Vesuvio Café read, “Don’t envy beatniks . . . Be one!” (Henri Lenoir, the proprietor of Vesuvio and two other bars, let young artists like Sam Francis and Fred Martin hang their works for sale on his walls.)

One day, while Vera and Sam were lunching together in the Berkeley cafeteria, a girl stopped by their table to say hello. Sam introduced her as Muriel Goodwin. She had short, wavy, dark hair, a round face, and inviting brown eyes. She was a fellow artist. After she left, Vera asked Sam if he was dating Muriel. Instead of answering, Sam changed the subject, but his gaze followed Muriel as she wound her way among the tables, books balanced on one hip. Vera had the distinct impression that something was cooking between Sam and this new young woman.

She was right. Sam and Muriel had met in Erle Loran’s painting class after he’d playfully stolen her stool. When she confronted him, demanding the return of the stool, Sam gave her a paintbrush. Their flirtation blossomed into a romance. Twenty-one-year-old Muriel was from Modesto, California. She’d grown up with a self-sacrificing mother who taught migrant workers and a father who frequently abandoned the family when he went on drinking binges. Of her childhood, Muriel retained two vivid memories: religious programs continuously blaring on the radio, and her mother coming into her bedroom, fumigating the air with DDT. Muriel had married young to escape her family but divorced after only two years. A former kindergarten teacher, she had a patient, serene, and modest nature, which balanced with Sam’s fervent self-confidence. A student of Buddhism, she spoke extemporaneously, but gently and deeply, about poetry and art. To Sam, she was luminous.

That summer, after he graduated with his MA, a fire ripped through his father and stepmother’s home in Palo Alto. Caused by an explosion, it burned so hotly that the toilet melted. Everything, including more than one hundred paintings Sam had stored in a spare room, was destroyed. Though Sam was grateful that his father and stepmother had escaped the blaze and no one was hurt, he was devastated to learn that most of his artwork up through 1949 was ash.

On the heels of this disaster, a grief-stricken Sam sought consolation not from his new love interest, Muriel, but from Vera. If Muriel represented fresh desire, Vera was a familiar connection to the past. This pat- tern of seesawing between women would repeat for the rest of his life. Suspension was his most comfortable state. And it’s interesting to note that, just as Sam oscillated between Vera and Muriel, he drifted between the influences of painters at UC Berkeley, on one side of San Francisco Bay, and the California School of Fine Arts, on the other.

Unfortunately, when Sam appeared at Vera’s apartment looking for sol- ace, he did not find her ready with open arms and sympathy. Instead, she was embracing a man named Buzz Fulton. Fulton was Sam’s physical opposite, tall and dashingly handsome compared to the compact, robust Sam with a brace around his leg.

Perhaps Sam shouldn’t have had a double standard and have expected Vera to hold a torch for him. Yet in his vulnerable state, he was unprepared to see her smitten and hand in hand with another man. Vera was his vic- tory girl. He’d turned his back, just like he had when he was a child and his mother fell ill, and, when he looked around again, Vera, too, was gone. Even though they were separated and he was dating Muriel, Sam felt betrayed. Bursting into a fit of rage, he yelled at both Vera and Fulton and stormed off into the night.

With much of his artwork lost and his connection with Vera severed, even his country and campus felt alien. The dark grip of McCarthyism had taken hold. The UC Board of Regents was demanding that faculty members take an oath stating that they were not members of the Communist Party. His professor Margaret Peterson resigned her position. For a short time, Sam had belonged to the American Youth for Democracy. While not a communist organization, the group advocated student rights and battled rac ism. It was an offshoot of the Young Communist League of the war era.

For years, perhaps since his mother died, Sam’s compass had been pointed toward Paris. Though Clyfford Still had told his students at the California School of Fine Arts to throw off the ties of European heritage, he had also advised they bypass New York—it was too corrupt—and assert their independence by going to Paris. Henry Miller proclaimed the joys of self-liberation. Sam determined to start over. He’d learned from years of confinement that, regardless of attachment, regardless of trauma, there was sheer joy in moving, in pressing forward and seeking what was over the horizon.

Though Sam intended only a short stay abroad, he would not return to live in California for twelve years. By then, he had twice circumnavigated the globe. In 1950, when he set out for Paris at age twenty-seven, he shed the last layer of his chrysalis. As a sign of emancipation, he threw away his corset and his leg brace. Like many young American men, he was bankrolled by the GI Bill. He did not travel alone. Muriel was by his side. “I wanted to get out of the country,” he said. “Out of myself. To have a look at myself.”