By Ross Cole, author of The Folk: Music, Modernity, and the Political Imagination

If you’ve ever watched Werner Herzog’s brilliant but harrowing film Grizzly Man, you might recall the closing song––‘Coyotes’ performed by Don Edwards. It emerges just after Herzog’s parting comment that footage of bears running wild in their state of innocence offers a glimpse into the darker recesses of our own nature.

I happened to re-watch Grizzly Man over the summer of 2019 as I was writing a new book, The Folk: Music, Modernity, and the Political Imagination. One of my habits, as is sometimes the case with a song I love, was to listen to ‘Coyotes’ on repeat as I typed. At first this was entirely unrelated to the book, but over time I came to see just how pertinent it is to the topic.

‘Coyotes’ is an elegy. It is a song of loss, of longing and regret. Sung from an onlooker’s perspective, it eulogises a disappearing world––of red wolves and frontiersmen, dusty trails and independence, outlaws and adobe walls, moons crossing mountains (things familiar to readers of Cormac McCarthy). The figure Edwards sings about can find no place in a brave new world of asphalt and steel. By the end of the song, he’s merged with the landscape, turned feral, and become one more coyote wailing under the clear skies of south Texas. He is history, myth, and nature rolled into one.

This, in essence, is the confluence I set out to map in The Folk. The book traces these elusive figures back to a pivotal moment when they were cast as symbols of modernity’s changing pace–potential saviours, indexes of longing, ciphers of belonging. As such, they are inherently political. Animated by collectors and commentators, the folk suggested ways of thinking about society and culture in relation to that tantalizing concept “the people.”

What interests me is how and why a sympathy for the folk sent writers in radically different political directions. William Morris, for one, titles the penultimate chapter of his visionary novella News from Nowhere “An Old House amongst New Folk.” For Morris, the folk and the artisanal ideals they embody provide imaginative impetus for a utopian future in which alienation and exploitation vanish. In contrast, Cecil Sharp viewed the revival of English folk song and dance as a mechanism for mass social reform that could resist increasing urban “cosmopolitanism.” Fed to children in schools, native folk songs were intended to unite the nation on racial terms through what he calls “the subtle bond of blood and kinship.” Whether Marxist rebellion or fascist revolution of the spirit, The Folk encourages us to think of such visions as inherently entwined, voicing the imperatives of possible worlds.

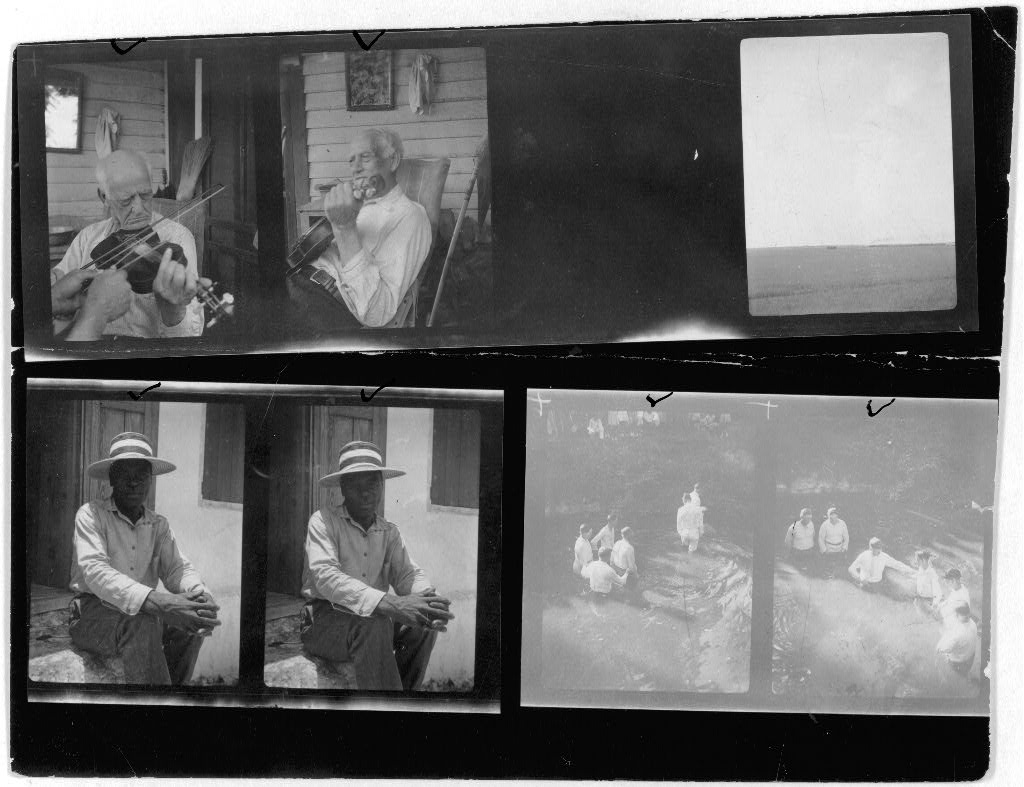

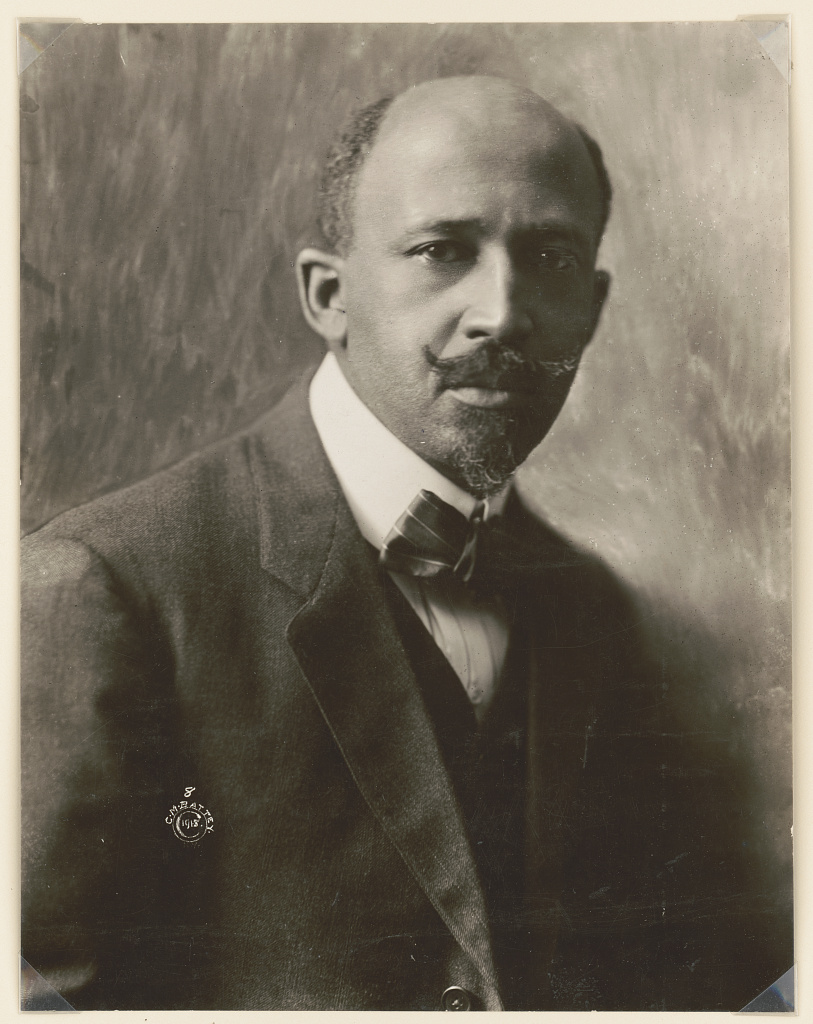

Central to The Folk is a desire to bring these diverse histories together. Most significant in this respect is the fact that the folk have too often found themselves consigned to a segregated narrative. African American creative practice around the turn of the 20th century is imbued with a folkloric spirit as an act of remembering––of attempting, quite literally, to re-member a race, bringing together the scattered remains of a social body torn apart by the traumatic legacies of slavery. And yet here too we find differences in how the folk were received. For Jean Toomer, for instance, traces of the past were precious to the extent they bore witness to an identity that would soon fade, fragment, and die. His novel Cane is an effort to resist modernization through a particular kind of melancholy even as it assimilates modernist techniques into its fabric. By way of contrast, W. E. B. Du Bois’s The Souls of Black Folk is imbued with optimism. His “singing book” manifests the desire to establish a modern Black community out of the scattered ruins and atrocities of the American story.

What I argue is that the folk have always presented us with this double-edged sword. As products and paradigms of colonialist thought, they cut both ways, enabling nationalist projects of liberation just as easily as they can accommodate violent dreams of Volksgemeinschaft or the alt-right’s racist ideologies. The way out of this struggle involves recognising two things. First, that the folk are the fruit of our imagination and so naturally give rise to a variety of conflicting political ideas. And second, that the largely forgotten or downplayed histories lying behind such acts of imagination are hybrid at the root.

To return to ‘Coyotes,’ border regions like those portrayed in the song have always been our best teachers when it comes to the puzzling truth about culture––that it is a wild and untameable exchange of ideas, materials, and practice. ‘Coyotes’ is the kind of song that John Lomax might have been tempted to collect, assuming it to be an old cowboy ballad improvised in oral circulation. He would have been disappointed to know the truth. It isn’t even by Don Edwards, whose recordings now inhabit the Library of Congress. It is in fact by the professional songwriter Bob McDill, author of several country hits over the course of his 30-year career. This, of course, would not have surprised an astute folklorist such as Louise Pound or Lucy Broadwood, who were well aware of the impure history of popular culture. If The Folk teaches us anything about human nature it is that this simple truth is far less appealing than the myriad myths we enjoy spinning around remnants of the past.