We’re proud to share that author Jennifer Holland has won been awarded three prestigious awards from the Western History Association for her book, Tiny You: A Western History of the Anti-Abortion Movement!

The book won the Armitage-Jameson Prize for best scholarly book in western women’s and gender history; the David J. Weber prize for the best non-fiction book in southwestern history; and the W. Turrentine Jackson Award for the best first book in the history of American West.

In this interview with Holland, we take a deeper look at the book, including what motivated the project and how the book’s insights have continued to be especially relevant through the recent restrictions around abortion access in the U.S.

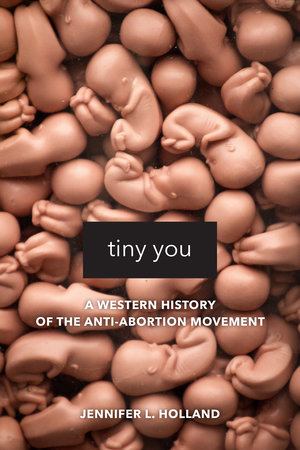

Tiny You tells the story of one of the most successful political movements of the twentieth century: the grassroots campaign against legalized abortion. While Americans have rapidly changed their minds about sex education, pornography, arts funding, gay teachers, and ultimately gay marriage, opposition to legalized abortion has only grown. As other socially conservative movements have lost young activists, the pro-life movement has successfully recruited more young people to its cause. Jennifer L. Holland explores why abortion dominates conservative politics like no other cultural issue. Looking at anti-abortion movements in four western states since the 1960s—turning to the fetal pins passed around church services, the graphic images exchanged between friends, and the fetus dolls given to children in school—she argues that activists made fetal life feel personal to many Americans. Pro-life activists persuaded people to see themselves in the pins, images, and dolls they held in their hands and made the fight against abortion the primary bread-and-butter issue for social conservatives. Holland ultimately demonstrates that the success of the pro-life movement lies in the borrowed logic and emotional power of leftist activism.

Jennifer L. Holland is Associate Professor of History at the University of Oklahoma and author of the award-winning book, Tiny You: A Western History of the Anti-Abortion Movement.

What motivated you to write Tiny You?

By the time I was coming of age, conservativism had reshaped both political parties and so many other parts of American life. And yet for a long time, historians of American politics were likely to tell the story of the liberal 1930s or the radical 1960s, not the conservative 1980s. Professionally I was inspired by scholars who started excavating the conservative past, especially Eric Avila, Lisa McGirr, Bethany Moreton, Michelle Nickerson, and Robert Self. I appreciated how those scholars denaturalized conservative politics by giving them origin points, visionaries, and narrative arcs.

On a more personal level, I was compelled to write Tiny You because of my own relationship to the politics of abortion. I had been a reproductive rights activist in college but some of my best friends were anti-abortion. One of them embraced all other parts of feminism but couldn’t support legal abortion. She had seen the anti-abortion film The Silent Scream in her Catholic Sunday school and that film never left her. I wanted to write a history about something I cared deeply about and my friend’s experience in Sunday school shaped the questions I asked. It was the intimate politics of the anti-abortion movement that I wanted to explore.

How does Tiny You help us to understand abortion in the current context, including the recent abortion ban in Texas?

Unfortunately it explains a lot. For forty years, there has been a gradual erosion of abortion rights in the United States but now we are approaching a precipice. I have little doubt that in the next year the Supreme Court will open the door wide for incredibly restrictive abortion laws. Such laws will likely ban abortion in half the country. Texas is only the first. Regions most changed by the anti-abortion movement, like the Intermountain West, the South, and the Midwest, will become abortion deserts. To turn back the tide of legal abortion, after fifty years of judicial precedent, is an incredible political feat.

Tiny You explains the movement that convinced so many Americans that ending abortion was the only political issue that mattered. For half a century, white religious conservatives brought arguments about fetal life and their anti-abortion ephemera into the intimate places of people’s lives. Over time, this political work—in homes, schools, churches, and crisis pregnancy centers—successfully changed many Americans’ sense of self, as well as their minds. Activists conceived of legal abortion as a genocide akin to the Holocaust and a dehumanization akin to American slavery. Those politics invited white people to think of themselves as abolitionists and the nation’s saviors, but also victims like the fetuses they sought to defend. The people who embraced these politics elected anti-abortion legislators and compelled those elected officials to nominate anti-abortion judges and justices.

What is the one message you hope readers take away from the book?

I hope readers see the power of activism in this book. No matter how many times the anti-abortion movement says things like “religious people are pro-life” or “abortion harms women” or “Republicans are pro-life,” this book should show that those are political claims that have evolved over time—even within the movement itself. I hope readers feel disoriented when they step back into the 1960s, a time when the anti-movement was small and not particularly powerful and when most Americans were skeptical of religious movements cementing their beliefs in law. I hope that historical vertigo reminds readers that an equally different future is possible, one with more rights and more justice, not less.

What are you working on now?

I am just beginning a project on the anti-gay movement, with special attention to battles in the American West. Unlike the anti-abortion movement, the anti-gay movement had no single goal; it moved from opposing anti-discrimination laws to banning gay teachers to restricting arts funding to outlawing gay marriage (plus many other stops along the way). This project will focus on the sinews connecting these formal political campaigns and the intimate expressions of those politics in queer people’s lives. While focusing on anti-gay activism, abortion politics will be in this book too, though in the background. After all, socially conservative activists envisioned abortion and homosexuality as the greatest threats to modern society, both touching off anxiety about those who failed to form families and reproduce in traditional ways. A recent amicus brief from Texas Right to Life to the Supreme Court in Jackson Women’s Health v. Dobbs reminds us of the vital connection. In it, the group requested that the court overturn Lawrence v. Texas (which made sodomy laws unconstitutional) and Obergefell v. Hodges (which legalized gay marriage across the country) alongside Roe v. Wade.