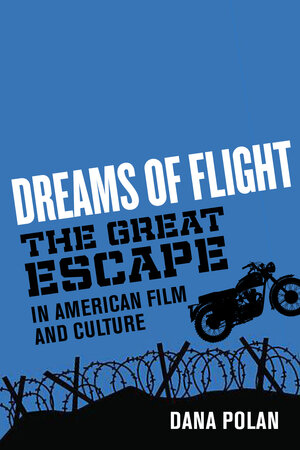

By Dana Polan, author of Dreams of Flight: “The Great Escape” in American Film and Culture

I had long wanted to revisit the 1963 classic The Great Escape, ever since seeing it as a kid at a drive-in re-release in the mid-60s. Like many young American boys of the time, I imagine, I went to the film for the gung ho promise of its canonic poster, “The great adventure, the great entertainment, the great escape.” Instead, I was blown away by a narrative that seemed to me to be a deflation of adventure — a transformation of rousing entertainment into something questioning and quite bleak.

The Great Escape’s downbeat turn from a fun romp into fatalism left a lasting impression on me, one that motivated my new book, Dreams of Flight: The Great Escape in American Film and Culture. As I write in Dreams of Flight, this unexpected narrative turn was a theme I began to notice in other films of that historical moment — one that is telling of American culture in the 1960s.

I have always imagined that my experience of movies is not mine alone but is likely representative of demographic currents I have been inscribed within and may be shared by others in the same demographic. At the time, I was a pre-teen American boy who especially liked “manly” action cinema and expected from the trailers and posters that The Great Escape fit that mold. I know from other fan accounts that I was not alone in feeling something disturbing and consequential was going on instead —in the film and in the times themselves. In my research for Dreams of Flight, I reached out to other viewers who first saw The Great Escape in the 1960s and found many had comparable reactions.

The Great Escape looks back to a golden Hollywood of action entertainment, but it also is arguably very much a Sixties film — with all the doubts, tensions, contradictions that characterize that period. As a last gasp of the old Hollywood, The Great Escape references a tradition of consummate escapism but it is very downbeat and un-escapist, both metaphorically and literally, in its overall take on history and masculine endeavor.

With its ensemble cast efforts—combined with stand-out stars like Steve McQueen—high production values, and adept crafting of nail-biting suspense, The Great Escape might well seem like a film appealing to those nostalgic for an older Hollywood, one referred to wistfully as “the kind of picture they just don’t make any more.”

Yet there are two problems with this kind of thinking. First, rousing male adventures are still being made and many don’t revise the ideology of the older model. And second – and this is dominant in my own approach to the film – I don’t think that The Great Escape really is as rousingly gung ho as all that. It’s not easily and cheerfully an adventure film. Three years into that fraught decade that was the 1960s, The Great Escape already evinces some of that despair about – and even downright questioning of – the adventure of war that would run through the period.

Of course, The Great Escape is not so much a battles-in-war movie as a prisoner-of-war movie, and here too, I think the film is very much of its times. In the 1960s, the idea of the human condition itself as a sort of entrapment or imprisonment is quite common in popular (and high) culture. Interpretations ranged from the metaphysical (to exist is to be stuck in a constraining sort of being-ness) to the more social (the Establishment sets out to lock up – and stamp out – all advocates of the unique and the different and the non-conformist). So although The Great Escape is in many ways a throwback to rip-roaring adventure of the traditional sort, it also has strong moments of bitter recognition of the walls that hold us in, of the fences that entrap us.

I wrote my manuscript while hunkering down during the COVID-19 pandemic, and I was struck continually by the extent to which themes of escape ran through popular media in such a fraught moment. To take just one example, when The Guardian listed fifty books that could “take you away from lockdown ” (accompanied by an image of one man reading outside on a balcony while others parachute off into space), it titled its annotated list “The great escape: 50 brilliant books to transport you this summer.”

As I write these lines, there’s also a nagging insistence by many people that they’d really, really like to get out, get away, get to a new normal – or use the crisis to rebuild life in new, responsive ways. And there’s also a new concern by many of those in quarantine to turn to culture (books, films, television shows, etc.) for what is often pointedly termed “escapism.” In all this, The Great Escape lingers for me, as a memory but also an ongoing pursuit, a consummate work of popular entertainment that digs deeply into resonant cultural motifs.

This post is part of our #SCMS22 series. Conference attendees can get 40% off the book with code 21E5879.