By Annie Berke, author of Their Own Best Creations: Women Writers in Postwar Television

At a recent book event– co-hosted with Liz Clarke, author of The American Girl Goes to War– one participant asked: “How did you decide what to put in the book and what to leave out?”

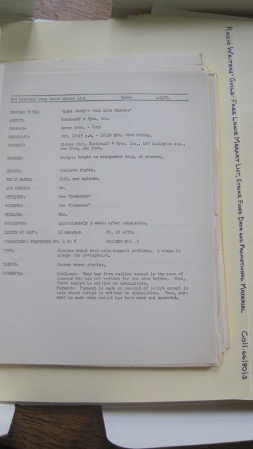

Having relied on archival evidence and materials to forge my book’s arguments about women writers for postwar television, I took thousands of photographs at libraries and paper collections across the United States. So my mind immediately went to the one memo that got away— or, more accurately, the one that I had to let go. This entry from the Radio Writers’ Guild Free Lance Market List was one of my most precious artifacts, the crown jewel of my book— until it wasn’t.

I found a lot of newsletters like this in the collection, and they gave me insights into the range of shows — some well-known, some obscure — being produced for radio and television. In April of 1951, “Aunt Jenny’s Real Life Stories” (CBS Radio, 1937-1956) was seeking out scripts with female protagonists and stories centered on “women’s problems.” No surprise, considering that the sponsor, Lever Brothers, was looking to sell their baking product (Spry shortening). Their target viewer-consumer would likely be a white, middle-class housewife looking to see her life and experiences reflected on-screen. But what did stop me short was the sponsor’s specification under “Taboos”: “No Career Women Stories.”

In Their Own Best Creations, I examine these women writers’ public personas together with the scripts and stories they wrote. What did they say in their interviews that they couldn’t say in their shows? What feelings could their fictional counterparts voice that they, as “real life” women, could not? I trace the “scripted life” of the woman television writer over the course of the decade, analyzing how this formulation crystallizes the contradictions of postwar femininity and anticipates many of the concerns of the second-wave feminism to come.

No. Career. Women. Stories. Discovering this document felt like I had uncovered the smoking gun of my monograph. Finally: a definitive, air-tight justification for my claim that these stories of homemakers were, in fact, treating larger issues of women’s creative agency, autonomy, and professional empowerment. Perhaps that inner declaration – I’ve cracked it! – should have been the first sign that it was too good to be true.

My disillusionment with this find was not dramatic but gradual. I started to wonder: why no career women stories? Was it as sexist a note as I initially suspected? Or did the show already have too manycareer women stories in production already? What did this 1951 notice from a single radio program tell me about the field of television writing across the entire decade? How many women writers even read this? And how many shows were outwardly hostile to career women stories, and how many sought such stories out? I started to wonder if I was reading into this memo, desperate for proof that these conservative storylines offered progressive, even subversive, solutions for “the problem that has no name”; better still, that everyone was in on the scheme. (Man, wouldn’t that be convenient?)

This memo was a bombshell discovery — for an argument I wasn’t making. In Production Culture, John Thornton writes that “the industry is not a monolith,” and I repeatedly encountered this in my research. Some women claimed to be turned away from writing jobs based on gender, while others said they were hired because the show wanted female representation on-staff. While I love this entry in the Free Lance Market List, I knew it wasn’t a part of the story I was telling. My focus had to remain on the strategic self-disclosures of women writers in this period, both those they spoke as themselves and those words they ventriloquized through their characters. Regardless of what I found in that folder that day, the fact remains: in my book, yes, they areall career women stories.

This post is part of our #SCMS22 series. Conference attendees can get 40% off the book with code 21E5879.