This post is part of our AMS 2020 conference blog series. Check out our virtual exhibit page for more.

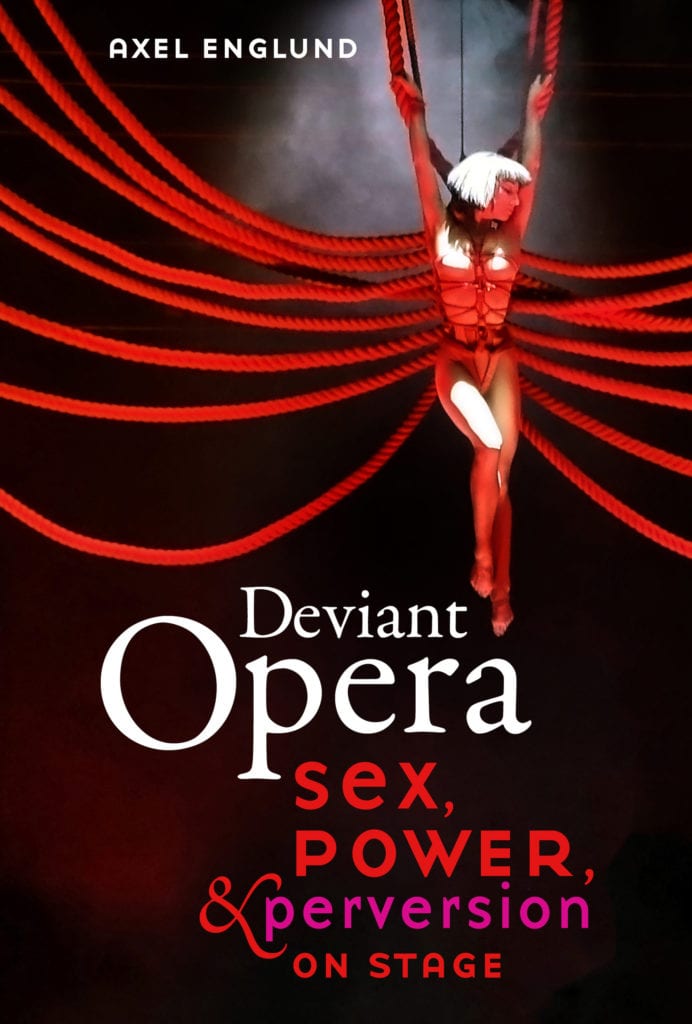

By Axel Englund, author of Deviant Opera: Sex, Power, and Perversion on Stage

The camera is rolling. Here is a middle-aged, bald nerd in thick glasses sitting at his mother’s kitchen table. As he pushes the button of the cassette player, a low-fi piano recording delivers the accompaniment of the “Habanera” from Carmen. He nervously clears his throat––equally aware perhaps of Maria Callas’s gaze from the framed photograph behind him and ours before him––and while his aging mother brings him a glass of milk and a sandwich on a tray, he starts singing about the rebellious bird of love.

This scene opens the first of three short films entitled MeTube, directed by Daniel Moschel (2013–2020). All are among my favorite gems of online hilarity. As the clip continues, Carmen’s familiar riff on love’s lawlessness is borne out and then some. In all of the MeTube clips, the everyday tedium of the nerd (played by tenor August Schram) is transformed into an ecstatic celebration of boundless desire. Starting out in the ordinary world, they are soon peopled by BDSM buffs and fetish fashionistas, crossdressing exhibitionists and extravagantly queer club crowds, and everyone is dancing to disco remixes of operatic earworms, accompanied by musicians donning latex face masks, leather thongs, or rubber ball gags.

This transformation is the work of opera. That old freak of an art form––now well into its fifth century––comes across as the gateway to a magical world of sensuality and eroticism, where the most scandalous fantasies become reality. Though presented with exceptional ingenuity by Moschel, this idea is not taken out of the blue. Throughout its history, opera has repeatedly been suspected of catering to desires on or beyond the border of the socially acceptable. From the star castrati, whose voices were sometimes thought to effect sex changes and subvert heterosexuality, to the luscious eroticism of Wagnerian music drama, where fantasies of incest and infidelity flew into the face of bourgeois norms, the opera has been seen as an epicenter of perversion.

In the last few decades, though, this tendency has taken a specific shape on stage, which resonates with the kinkiness showcased in MeTube. Today, regular operagoers may find themselves intrigued (or infuriated!) by how often handcuffs, blindfolds, riding crops, whips, chains, latex, leather and rubber find their way into productions of Mozart, Wagner, Puccini, and other staples of the repertoire. My book Deviant Opera: Sex, Power, and Perversion on Stage was born from a combination of bewilderment and curiosity vis-à-vis this tendency. Where did this strange cultural phenomenon come from? What can it tell us about operatic works and operatic performance?

BDSM––today a widespread acronym describing bondage/discipline, dominance/submission, and sadism/masochism––has grown increasingly visible in mainstream culture at least since the 1970s, its popularity culminating with the books and movies of the Fifty Shades trilogy. During the same decades, the worldwide ascent of Regietheater or director’s opera––where stage directors radically reimagine and reinterpret canonical works––opened the stage to imagery from contemporary popular culture. With it, the visual codes of BDSM and fetishism entered a cultural institution that had spent much of its past guarding its own elite status. But the closer I looked at this phenomenon, the clearer it became that there is also a deep resonance between opera and those erotic fantasies and practices typically considered “deviant.”

Taken together, these stagings can be interpreted as a statement about opera’s affinity with sadomasochism. Without literally claiming that they are the same thing––they aren’t––this mode of staging spotlights how much the two have in common. As theatrical activities, opera and BDSM both rely on hyperbolic, self-consciously ritualized performances. Like that of BDSM, the performance of opera is negotiated and scripted beforehand, but in the end, it is the live event that justifies the preparations. The sensual pleasure of opera, most lavishly delivered by its voice, is always routed through plot: like BDSM, it enlists real bodies to represent the most preposterous fantasy scenarios, which are insistently played out at the intersection of gender, power, and eroticism. Ultimately, of course, both practices are aimed at producing pleasure––aesthetic and erotic, though in different degrees––for everyone involved, regardless of the role they play.

Like BDSM, moreover, the gender politics of opera is a fraught issue, which tends to polarize queer and feminist criticism. Claims of subversion have often been made on opera’s behalf, but just as regularly it is accused of misogyny (and stagings that emphasize sex and violence often aggravate this). In its onstage fiction, opera famously insists on killing the female leads to its most climactic music, and the hierarchies of its backstage reality are fertile ground for harassment and exploitation, as recent years have made abundantly clear. (Even the droll MeTube cannot close its eyes to Metoo-related issues: as the third film begins, a dirty old casting director gropes the auditioning soprano on the pretext of teaching vocal technique, but is immediately punished by the nerd’s mother, who inserts a probe-like gadget straight out of R2D2’s toolbox into his rectum.)

Opera and BDSM may both take place within a safe, sane, and consensual framework, but the power structures of the outside world can never be entirely shut out. The enactment of humiliation and cruelty is frequently haunted by its actual counterpart. The pleasure of opera, therefore, comes with a responsibility of communication not unlike that of BDSM. While opera’s offering of jouissance may draw on disturbing undercurrents, that offering is also one with its appeal for critical engagement with sex, power, and gender; without the former, there would be no incentive for the latter.

The uneasy combination of the sensual, the silly, and the sinister thus highlighted by this style of staging lies at the core of contemporary opera culture. If opera criticism wants to stay relevant to the twenty-first century, it needs to confront this truth head-on.